Cumbernauld (near Glasgow) isn’t a place I think of as exciting, but when I was there in March there was lots of excitement. I was attending the Scottish Association of Writers annual conference at a spa and golfing hotel. This is an amazing, fun event, full of the friendliest people imaginable.

Speaking as someone who likes their own company, I had a fabulous time meeting up with old friends, people I’ve only ever seen on zoom calls, people whose names I’d vaguely heard of, and more. The weather, unusually, was dry and clear. So dry and clear, in fact, that when the fire alarm sounded at 00:15 on the Sunday morning, I dashed outside wearing little more than a short cotton nightie and my glasses straight into the grip of a bitter frost! Within minutes it became clear this was not a drill – the laundry was on fire – and I was shivering violently.

Strange things go through your mind at times like this, and I was wondering how ironic it would be to escape from a contained, small fire only to die of hypothermia. Fortunately, a writer I’d met for the first time the day before came to my rescue. Another pocket novel writer had the presence of mind to grab her car keys (but not her shoes – interesting priorities there) and bundled me into her car. Then she found a spare fleece in her boot. Fortunately she found some shoes for herself in there, too.

Long story short, it was over two hours before we were allowed back to our rooms. The last hour of that was spent in the bar with the alarms still blaring as the management couldn’t switch them off until they’d dispersed smoke from the corridors.

Once back in bed, I put on my yoga pants and long socks, and then threw the unused half of the duvet over me, too. An hour later I was finally warm and sank into a far too short sleep. Here’s a picture of the crumpled space blanket the management evenutally gave me after they’d made those in cars get out so they could check everyone was accounted for.

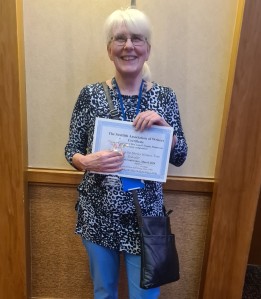

The previous day I’d won the humorous short story competition with a story I thought would never see the light of day. I only entered it in the spirit of taking part: the SAW conference hinges on it’s numerous competitions, and if people don’t enter, there’s not much of a conference! I wouldn’t have entered had I known I would subsequently have to stand in front of a packed room and read my Jane Austen, Conan Doyle, Life on Mars genre mashup aloud.

Anyway, I am now the very proud owner of the Margaret McConnel trophy for one year only. Here’s a picture of me holding it, along with my winner’s certificate. The trophy is a transparent sort of star bursting out of a pedastal, which is why it doesn’t show up well against the white certificate.

The adjudicator of the humorous short story competition, Ingrid Jendrzejewski, told conference not to get disheartened by rejections; you just have to find the right market at the right time. I think Shirley Holmes, Time Traveller embodies that because I have no idea where else I could have sent what started as a bit of fun just for me.

So, my message this month is don’t be dishearted by rejections. Make sure your work is as good as it can be, and keep looking for that perfect home. I’d had some feedback on Shirley Holmes from my WOMAG writing critique group, which I acted on and I’m sure that helped. This is why I keep emphasising the importance of networking and interacting with other writers. It really works.

If you’re stuck for places to send your work if the WOMAG’s don’t like them, why not sign up for Chris Fielden’s website and newsletter. He keeps a long list of markets and regularly sends news of short story competitions. He runs short story competitions, too.

If you’re a Scottish writer, or living in or near Scotland, why not join the Scottish Association of Writers? There is both group and individual membership available. Who knows, we might even meet up in Cumbernauld one year, but hopefully not in the carpark at silly o’clock.

If you would like to read Shirley Holmes, Time Traveller, click here. You’ll be asked to sign up for my newsletter list. I promise newsletters will be infrequent and only drop into your inbox when I have something exciting to share. You can unsubscribe any time anyway!